News Release from windfair.net

Wind Industry Profile of

US: Offshore Wind Industry off on a false start

A few weeks ago the Americans were able to report at last: The first foundation for an offshore wind farm in US waters was installed off the coast of Rhode Island. Hopes were great that this event would create a momentum to give the entire offshore wind industry in the United States the much-needed impetus to ensure future growth.

A few weeks later disenchantment has returned to the industry. While installations works at Block Island are in full swing, it is not going smoothly with other projects.

The reasons for this are manifold. For many years, the Cape Wind offshore wind farm was the flagship project in the US. Developers repeatedly succeeded in Court against an endless list of opponents which made the entire US wind industry to expect the first offshore wind farm will indeed be built off the coast of Massachusetts. Even as other projects such as Block Island or the Fishermen's Energy project in New Jersey gained first successes in form of licenses and finished financing their projects, yet all believed that Cape Wind will win the race for the first offshore wind farm at the end. All the greater was the shock for the industry when it suddenly said earlier this year that two utilities got out of their contracts with Cape Wind again, because funding was not secured. To date, the reputation of the American offshore pioneers has not recovered from this blow.

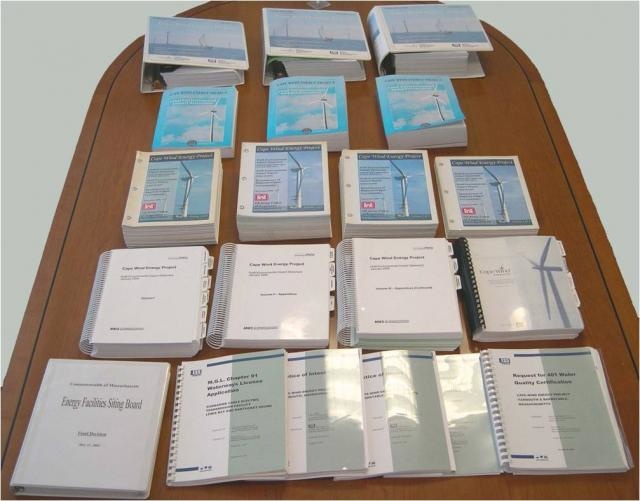

Licensing documents for Cape Wind project (Source: Cape Wind)

The Block Island project on the other hand has been designed but in completely different dimensions from the beginning. While this is only a small test park with five turbines, Cape Wind was aimed at commercial use from the start: 130 turbines should provide a total of 430MW power. This project would not only have served to underpin the proper functioning of the turbines, but even show more far-reaching mechanisms such as marketing of renewable energy for tens of thousands of people.

The preliminary failure of the project, however, currently still makes many companies shy away from investing in offshore wind industry. Professor James Manwell, director of the Wind Energy Centre at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, states on the Australian news site news.com.au: “Since Cape Wind seemed to be tip of the spear, slowing Cape Wind sort of slowed everybody down.” Even Jim Gordon, CEO of Cape Wind, had to admit: "There wasn't a prescribed path in which to do this. We knew it would take several years, but we never expected it to take this long."

Jeff Grybowski also has had similar experiences at Block Island. In addition to obtaining necessary permits, it has also taken a long time to find the right suppliers in the US, because skepticism was high.

The exceptions are two companies named Keystone Engineering and Gulf Island Fabrication from Louisiana. "It was a nice bit for two Louisiana companies who have been in the oil and gas industry for more than 30 years to put their experience together and try to come up with a solution,” Kirk Meche, president and CEO of Gulf Island, told The Advocate. The two companies worked together on the design of the jacket foundations for Block Island and finally produced five jackets.

But Meche also knows why other companies are refraining from expanding into the new industry: “You've got five platforms out there trying to generate 30 megawatts of power. When we talk about trying to generate 250 to 300, a lot of people start paying attention.” In his view the industry is simply too small to be taken seriously at the moment.

The first jacket foundation for Block Island is lowered into the water (Source: Jeff Grybowski)

Another problem that paralyzes the US offshore industry are uncertainties in politics. While President Barack Obama has explicitly named onshore and offshore wind in his climate plan, however, regulatory obstacles remain high – and vary from federal state to state. Developers blaim the lack of so-called ORECs, Offshore Renewable Energy Certificates, which are issued by the federal state and include some kind of guarantee for the purchase of electricity. Without such a certificate, local energy suppliers don't want to sign contracts with offshore developers. The Fishermen's Energy project has to deal with these difficulties at the moment, so that construction of the offshore farm off the coast of Atlantic City is further delayed.

And so it seems ambivalent that the federal state of New Jersey still wants to hold another auction this year to build more offshore wind farms, but conditions for the actual construction haven't improved so far. "The lease is not valuable unless there is a state policy supporting offshore wind," Grybowski criticized at North American Windpower.

But the potential for offshore wind energy in the US remains very high, alone the waters off New Jersey have an expected capacity of 3,4GW. When this unused energy can be harvested on a large scale is still unknown though.

- Author:

- Katrin Radtke

- Email:

- kr@windmesse.de